Entrepreneur and Business Resources

Integral Methods and Technology

Governance and Investor Responsibility

|

The Balanced Scorecard and Corporate Social Responsibility: Aligning values for profit

CSR reporting has grown over the past few years, but the information provided by those reports isn’t always used for strategic advantage. Tying values and measures to a Balanced Scorecard could be the way to make good intentions more profitable

By David Crawford, CMA, and Todd Scaletta, CMA

The

corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement has been gathering momentum

for the past 10 years. This growth has raised questions — how to define

the concept, how to measure it, and how to make good on its promises.

The Dow Jones Sustainability Index created a commonly accepted definition

of CSR: “a business approach that creates long-term shareholder value

by embracing opportunities and managing risks deriving from economic,

environmental and social developments.” This definition encompasses a

broad range of corporate values and concerns, including reputation, transparency,

social impact, ethical sourcing, profitability and civil society — the

list goes on. As a result of the interdependent nature of CSR, integration

of its values remains a challenge for many organizations.

The

corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement has been gathering momentum

for the past 10 years. This growth has raised questions — how to define

the concept, how to measure it, and how to make good on its promises.

The Dow Jones Sustainability Index created a commonly accepted definition

of CSR: “a business approach that creates long-term shareholder value

by embracing opportunities and managing risks deriving from economic,

environmental and social developments.” This definition encompasses a

broad range of corporate values and concerns, including reputation, transparency,

social impact, ethical sourcing, profitability and civil society — the

list goes on. As a result of the interdependent nature of CSR, integration

of its values remains a challenge for many organizations.

One of the fundamental opportunities for the CSR movement is how to effectively align consumer and employee values with corporate strategy to generate long-term cognizant benefits — a better understanding of precisely with whom, what, when, where, how and why an enterprise makes a profit or surplus. CSR requires more holistic strategic thinking and a wider stakeholder perspective. Because the Balanced Scorecard is a recognized and established management tool, it is well positioned to support a knowledge-building effort to help organizations make their values and visions a reality. The Balanced Scorecard enables individuals to make decisions daily based upon values and metrics that can be designed to support these long-term cognizant benefits.

A simple definition of a Balanced Scorecard is “a focused set of key financial and non-financial indicators.” These indicators include both leading and lagging measures. The term “balanced” does not mean equivalence among the measures but rather an acknowledgement of other key performance metrics that are not financial. The now classic Balanced Scorecard, as outlined by Robert Kaplan and David Norton, has four quadrants or perspectives — (i) people and knowledge, (ii) internal, (iii) customer and (iv) financial.

For example, increased training for employees (people and knowledge) can lead to enhanced operations or processes, (internal) which leads to more satisfied customers through either improved delivery time and/or lower prices (customers), which finally leads to higher financial performance for the organization (financial).

As CMA Canada’s Management Accounting Guideline Applying the Balanced Scorecard states:

Managers can use the Balanced Scorecard as a means to articulate strategy, communicate its details, motivate people to execute plans, and enable executives to monitor results. Perhaps the prime advantage is that a broad array of indicators can improve the decision making that contributes to strategic success... Non-financial measures enable managers to consider more factors critical to long-term performance.

Cause and effect: CSR’s competitive advantage

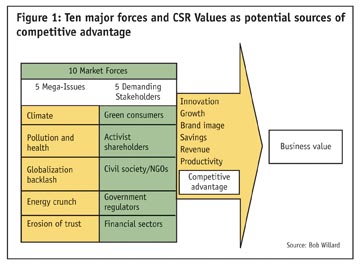

Bob Willard’s book The NEXT Sustainability Wave outlines a starter set of 10 major market forces that are driving the need for organizations to address CSR in a credible manner. Willard’s 10 major forces are divided between mega-issues and the stakeholders who are demanding change. These forces are motivating companies to change their behaviour and use CSR as a strategic instrument. The 10 major forces are:

Five Mega-Issues:

- Climate change

- Pollution / health

- Globalization backlash

- The energy crunch

- Erosion of trust

Five Demanding Stakeholders:

- Green” consumers

- Activist shareholders

- Civil society / NGOs

- Governments and regulators

- Financial sector

Willard goes on to explain how these forces create increased exposure and awareness to business challenges and opportunities. The actual effect of these challenges and opportunities was recently identified in KPMG’s International Survey of Corporate (Social) Responsibility Reporting 2005. This report surveyed more than 1,600 companies worldwide and documented the top 10 motivators driving corporations to engage in CSR for competitive reasons, which are:

- Economic considerations

- Ethical considerations

- Innovation and learning

- Employee motivation

- Risk management or risk reduction

- Access to capital or increased shareholder value

- Reputation or brand

- Market position or share

- Strengthened supplier relationships

- Cost savings

By creatively responding to these market forces, and others generated by the CSR movement, organizations can reap considerable benefits.

There are many examples of how companies are being affected by CSR drivers and motivators. The following three examples are just a brief sample of the myriad CSR performance motivators that are top-of-mind for executives.

1. Working with stakeholders

Driver number six in KPMG’s list access to capital or increased shareholder value, acknowledges that organizations able to identify, understand, mitigate and report their business risks have a competitive advantage when raising capital. A good example of this is the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP — www.cdproject.net), which was developed, implemented and is monitored by a group of institutional investors representing in excess of US$20 trillion in capital. For the past three years, the CDP has polled the FT500, which represents the world’s 500 largest companies, requesting a response to a climate change questionnaire. “Companies failing to respond or providing weak responses... will invite particular scrutiny from the investment community,” said James Cameron of the CDP. According to the CDP, its institutional investors use the questionnaire results to assess company plans and performance for addressing the potential risks and opportunities of climate change.

2. Cultivating green consumers

Ethical considerations, KPMG’s second driver, is directly linked to the Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability (LOHAS) market. LOHAS describes a US$226.8 billion marketplace for goods and services focused on health, the environment, social justice, personal development and sustainable living. The consumers attracted to this market have been collectively referred to as cultural creatives and represent a sizable group in the U.S. Approximately 30% of the adults in the U.S., or 63 million people, are currently considered LOHAS consumers. These consumers represent a substantial amount of buying power since they tend to have higher disposable income and are willing to seek out products and services that meet their CSR values and corresponding ethical concerns. Examples of products in this marketplace include organic foods, hybrid vehicles and fair trade coffee. It’s also important to note that LOHAS consumers bring their CSR values to their workplaces.

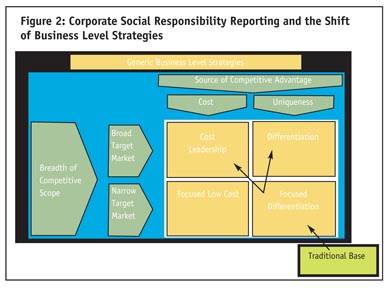

The strategic shift of organizations from a niche

market (focused differentiation strategy) for green consumers to a broader

appeal is occurring, which can be illustrated in a generic manner, as Figure

2 shows.

LOHAS Consumers reward enterprises that demonstrate the values they seek (buy products and speak positively) and punish organizations that do not (refuse to buy products and speak critically about). In essence, these consumers/employees pay close attention to how their values align with producers of goods and services, their employers and even the charities they support.

The move to a broad market differentiation strategy can be achieved through extensive knowledge of green consumers, as well as the fulfillment of their information needs through appropriate reporting. At the same time, moving to a cost leadership strategy involves the effective and efficient use of resources, as the next example will illustrate.

3. Banking on the bottom line

The first and last of KPMG’s drivers, economic considerations and cost savings, reinforce the old adage “you can’t take the top line and put it in the bank; you can only put the bottom line in.” An added benefit of a CSR reporting focus is the ability, through it, to understand, measure and improve the use of resources.

For example, reduction in use of energy and materials will provide an enterprise with improved bottom line performance and a competitive advantage through a lower cost structure. The first two of the “three Rs” (reduce and re-use) can lead to substantial savings for organizations that implement an effective performance measurement system. The Scottish Environmental Protection Agency recently estimated that businesses in Scotland could increase their annual profits by as much as $2,000 per employee through the introduction of aggressive waste reduction, energy efficiency and recycling programs.

CSR reporting requirements

The opportunity to grow the top line through green consumers in the LOHAS marketplace comes with the price of increased transparency — this customer group demands the necessary data to make informed decisions. Interested stakeholders, such as employees, regulators, investors, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are pressuring organizations to disclose more and more CSR information. Companies in particular are increasingly expected to generate annual CSR reports in addition to their annual financial reports.

CSR reporting measures an organization’s economic, social and environmental performance and impacts. The measurement of CSR’s three dimensions is commonly called the triple bottom line (TBL). The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is the internationally accepted standard for TBL reporting (See “Managing and reporting sustainability” in the February 2005 issue of CMA Management for more information). The GRI was created in 1997 to bring consistency to the TBL reporting process by “enhancing the quality, rigor and utility of sustainability reporting.”

Representatives from business, accounting societies, organized labour, investors and other stakeholders all participated in the development of what is now known as the GRI Sustainability Guidelines. The guidelines are composed of both qualitative and quantitative indicators. The guidelines and indicators were not designed, nor intended, to replace GAAP or other mandatory financial reporting requirements. Rather, the Guidelines are intended to complement GAAP by providing the basis for credibility and precision in non-financial reporting.

One of the key benefits for an organization using a Balanced Scorecard is improved strategic alignment. In their fourth annual CSR report, one company made an unexpectedly candid comment: “We strongly believe in the business case for corporate responsibility and reporting. However, there is more work to be done to more precisely quantify the benefits of these activities to our business.” The Balanced Scorecard can be an effective format for reporting TBL indicators, as it illustrates the cause-and-effect relationship between being a good corporate citizen and being a successful business.

The CSR virtuous cycle

Enterprises can use the combination of the Balanced Scorecard and CSR to help create a competitive advantage by letting decision makers know if they are truly entering into a CSR virtuous cycle — a cycle in which economic and environmental performance, coupled with social impacts, combines to improve organizational performance exponentially.

How is this accomplished? A company could begin to compete on cost leadership as a result of improved technology and effective and efficient processes, which leads to improved ecological protection, which results in better risk management and a lower cost of capital. Alternatively, a company could differentiate itself from its competitors’ values and performance as a result of its community building activities, which can improve corporate reputation, result in improved brand equity, creating customer satisfaction, which increases sales. The move to a broad differentiation strategy can also be achieved through extensive knowledge of green consumers and leveraging their information needs through appropriate CSR reporting to improve brand equity and reputation. These examples are designed to illustrate the interrelationship in an organization’s triple bottom line.

Several organizations have already recognized this powerful combination and have adapted or introduced a Balanced Scorecard that includes CSR elements to successfully implement strategy reflective of evolving societal values. Dow is one such company.

Dow’s CSR-Balanced Scorecard

Dow realized in the early 1990s that it could and should improve its social, environmental and financial performance. The company’s early focus (over an initial 10-year period) was on opportunities and challenges most commonly associated with environment, health and safety (EH&S). Dow achieved many of its early objectives by focusing on the low-hanging fruit. In 2003, the company began to create another series of initiatives to address opportunities and challenges over another 10-year period. These initiatives were created and refined after the company made a significant effort to consult with stakeholders to better understand internal and external expectations, with a specific emphasis on CSR. How to accomplish and measure their success was a major question the company had to answer. Dow’s answer to this challenge is clearly communicated in its 2003 Public Report:

To bring more balance into how we measure our success and progress on the integration of the Triple Bottom Line, Dow will launch a Balanced Scorecard.... The scorecard is published for employees, is updated quarterly and is the basic internal measurement tool for our progress on the Triple Bottom Line.

Dow uses the GRI methodology to create, monitor and measure its broad progress towards sustainability and specific corporate social responsibility commitments. Why is this important? If Dow really believed that sustainable development is a business priority in the 21st century, then it had to translate strategy into action. Dow chose to use Balanced Scorecard and CSR reporting to help accomplish this important task.

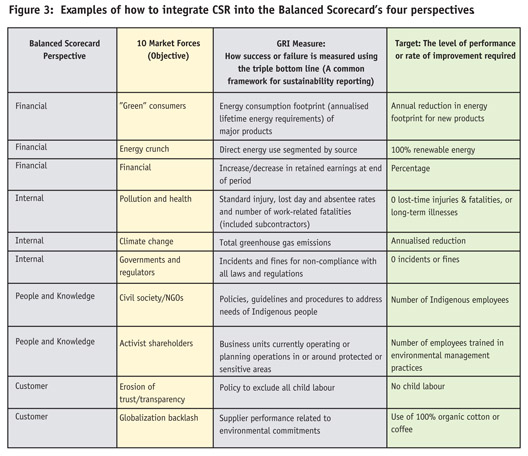

Figure 3 demonstrates how the Balanced Scorecard can be either introduced or adapted to strategically align an organization’s values with specific market forces. A variety of GRI indicators were selected and paired with Bob Willard’s 10 market forces to demonstrate the wide range of values that can be addressed through the Balanced Scorecard.

In a best case scenario, companies that either adapt and/or adopt a Balanced Scorecard that includes CSR elements could compete on either cost leadership or differentiation, or both — a very powerful combination that will enable them to enter the CSR virtuous cycle.

Is it actually possible to enter the CSR virtuous cycle? In response to intense public criticism about labour conditions in its factories, Gap Inc., for instance, fundamentally changed the way it manages labour issues. Is Gap’s record on labour issues perfect? No, but it is much improved as a result of protests from activist shareholders and the civil society movement. When asked why Gap would pursue improved labour standards in its factories, in February 2005, Dan Henkle, Gap’s vice-president of global compliance, stated that “not only labour standards in factories (improve) but also every other dimension of what’s really important: overall productivity, quality, absenteeism, turnover rates in factories, it’s really all connected.”

As identified earlier in this article, values play a large role in the decision making process for green consumers. How truly important are values to organizations? Jim Collins in his book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t identified that the companies he and his team classified as “great” had a few common characteristics. One characteristic was a vision to make a difference, rather than simply making a profit. Another characteristic was shared values. It didn’t matter what the values were, rather that there were shared values.

Many management accountants are familiar with the Balanced Scorecard, thus have a tool at their disposal to help them navigate the sometimes foggy worlds of strategy and CSR. The Balanced Scorecard can help organizations strategically manage the alignment of cause-and-effect relationships of external market forces and impacts with internal CSR drivers, values and behaviour. It is this alignment combined with CSR reporting that can enable enterprises to implement either broad differentiation or cost leadership strategies. If management accountants believe there will be resistance to stand-alone CSR initiatives, they can use the Balanced Scorecard to address CSR opportunities and challenges. Management accountants have the skills and tools to lead their organizations towards a CSR virtuous cycle of cognizant benefits, understanding precisely how and why their company’s profits are made.

David Crawford, CMA, CCEP, (dcrawford@mpsc.com) is the market and technical services manager at Manitoba Product Stewardship Corporation. Todd Scaletta, CMA, MBA, (scaletta@cc.umanitoba.ca) is an educator and partner with Scoperta Solutions, a management consulting company located in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The authors wish to thank Bob Willard for his assistance in the preparation of this article.