Entrepreneur and Business Resources

Integral Methods and Technology

Governance and Investor Responsibility

|

Emotion, neuroscience and investing: Investors as dopamine addicts

By James Montier

Global Equity Strategy: January 20, 2005

What goes on inside our heads when we make decisions? Understanding how

our brains work is vital to understanding the decisions we take. Neuroeconomics

is a very new field that combines psychology, economics and neuroscience.

That may sound like the unholy trinity as far as many readers are concerned,

but the insights that this field is generating are powerful indeed.

Before I head off into the realms of neuroscience I should recap some

themes we have explored before, but that provide the backdrop for much

of the discussion that follows. One of the most exciting developments

in cognitive psychology over recent years has been the development of

dual process theories of thought. Alright, stay with me now, I know that

sounds dreadful, but it isn't. It is really a way of saying that we tend

to have two different ways of thinking embedded in our minds.

Spock or McCoy?

For the Trekkies out there, these two systems can, perhaps, be characterised

as Dr. McCoy and Mr. Spock. McCoy was irrepressibly human, forever allowing

his emotions to rule the day. In contrast, Spock (half human, half Vulcan)

was determined to suppress his emotions, letting logic drive his decisions.

McCoy's approach would seem to be founded in system X. System X is essentially

the emotional part of the brain. It is automatic and effortless in the

way that it processes information. That is to say, the X-system pre-screens

information before we are consciously aware that it even made an impact

on our minds. Hence, X-system is effectively the default option. X-system

deals with information in an associative way. Its judgements tend to be

based on similarity (of appearance) and closeness in time. Because of

the way X-system deals with information it can handle vast amounts of

data simultaneously. To computer nerds it is a rapid parallel processing

unit. In order for the X-system to believe something is valid it may simply

need to wish that it were so.

System C is the "Vulcan" part of the brain. To use it requires deliberate

effort. It is logical and deductive in the way in which it handles information.

Because it is logical, it can only follow one step at a time, and hence

in computing terms it is a slow serial processing unit. In order to convince

the C-system that something is true, logical argument and empirical evidence

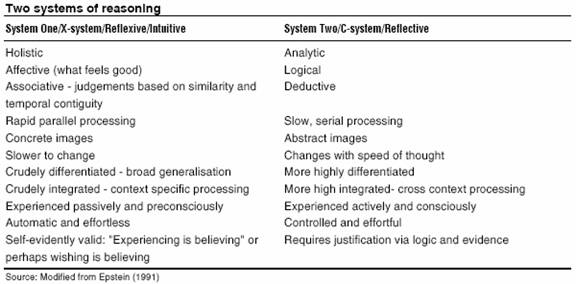

will be required. The table below provides a summary of the main differences

between the two systems.

This dual system approach to the way the mind works has received support

from very recent studies by neuroscientists. They have begun to attach

certain parts of the brain to certain functions. In order to do this neuroscientists

ask experiment participants to perform tasks whilst their brains are being

monitored via elector-encephalograms (EEG), positron emission topography

(PET) or most often of late functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The outcomes are then compared to base cases and the differences between

the scans highlights the areas of the brain that are being utilised.

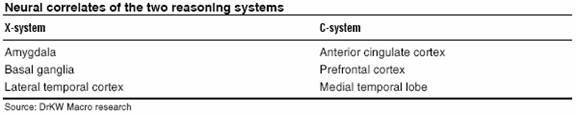

The table below lays out some of the major neural correlates for the two

systems of thinking that were outlined above. There is one very important

thing to note about these groupings - the X-system components are much

older in terms of human development. They evolved a long time before the

C system correlates.

The primacy of emotion

This evolutionary age edge helps to explain why the X-system is the default

option for information processing. We needed emotions far before we needed

logic. This is perhaps best explained by an example using fear. Fear is

one of the better understood emotions1.

Fear seems to be served by two neural pathways. One fast and dirty (LeDoux's

low road), the other more reflective and logical (the high road). The

links to the two systems of thinking outlined above are hopefully obvious.

Imagine standing in front of a glass container with a snake inside. The

snake rears up, the danger is perceived, and the sensory Thalamus processes

the information. From here two signals emerge. On the low road the signal

is sent to the amygdala, part of the X-system2,

and the brain's center for fear and risk. The amygdala reacts fast, and

forces you to jump back.

However, the second signal (taking the high road) sends the information

to the sensory cortex, which in a more conscious fashion assesses the

possible threat. This is the system that points out that there is a layer

of glass between you and the snake. However, from a survival viewpoint

a false positive is a far better response than a false negative!

Emotions: body or brain?

Most people tend to think that emotions are the conscious response to

events or actions. That is, something happens and your brain works out

the emotional response - be it sadness, anger, happiness etc. Then your

brain tells your body how to react - tear up, pump blood, increase the

breathing rate etc.

William James, the grandfather of modern psychology, was amongst the first

to posit that actually true causality may well flow from the body to the

brain. In James' view of the world, the brain assesses the situation so

quickly, there simply isn't time for us to become consciously aware of

how we should feel. Instead the brain surveys the body, takes the results

(i.e. skin sweating, increased heart beat etc) then infers the emotion

that matches physical signals that the body has generated.

If you want to try this yourself, try pulling the face that matches the

emotion you wish to experience. For instance, try smiling (see we aren't

always miserable and bearish despite our reputations). If you sit with

a smile on your face, concentrating on that smile, soon enough you are

likely to start to feel the positive emotions that one associates with

smiling3.

An entertaining example of the body's impact upon decisions is provided

by Epley and Gilovich4

(2001). They asked people to evaluate headphones. Whilst conducting the

evaluation, participants were asked to either nod or shake their heads.

Those who were asked to nod their heads during the evaluation gave much

more favourable ratings than those asked to shake their heads.

In the words of Gilbert and Gill5,

we are momentary realists. That is to say, we have a tendency to trust

our initial emotional reaction and correct that initial view "only subsequently,

occasionally and effortfully." For instance, when we stub a toe on a rock

or bang our head on a beam (an easy thing to do in my house), we curse

the inanimate object despite the fact it could not possibly have done

anything to avoid our own mistake.

Emotion: Good, bad or both?

However, emotion may be needed in order to allow us to actually make decisions.

There are a group of people who, through tragic accidents or radical surgery,

have had the emotional areas of their minds damaged. These individuals

did not become the walking optimisers known as homo economicus. Rather,

in many cases, these individuals are now actually incapable of making

decisions. They make endless plans but never get round to implementing

any of them6.

Bechara et al7

devised an experiment to show how the lack of emotion in such individuals

can lead them to make sub-optimal decisions. They played a gambling game

with both controls (players without damage to the emotional centres of

the brain) and patients (those with damage to the emotional parts of the

brain). Each player was sat in front of four packs of cards (A, B, C and

D). Players were given a loan of $2000 and told the object of the games

was to avoid losing the loan, whilst trying to make as much extra money

as possible. They were also told that turning cards from each of the packs

would generate gains and occasional losses. The players were told the

impact of each card after each turn, but no running score was given.

Turning cards from packs A and B paid $100, whilst C and D paid only $50.

Unpredictably, the turning of some cards carried a penalty. Consistently

playing packs A and B led to an overall loss. Playing from C and D led

to an overall gain.

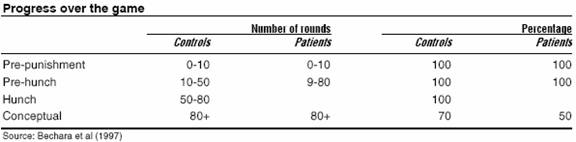

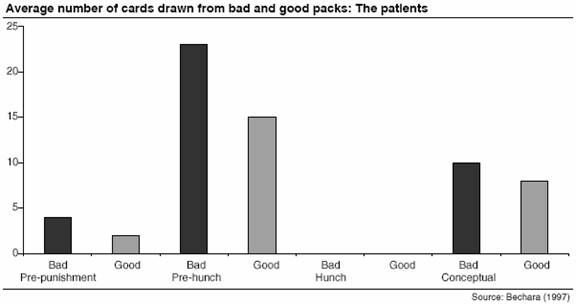

Performance was assessed at various stages of the game. Four different

periods were identified. The first involved no loss in either pack (pre-punishment);

the second phase was when players reported they had no idea about the

game, and no feeling about the packs. The third was found only in the

controls, they started to say they had a hunch about packs A and B being

riskier, and finally, the last phase when (conceptual) players could articulate

that A and B were riskier.

The table below shows the average number of rounds in each phase, and

the percentage of players making it through each phase of the game. The

patients were unable to form hunches, and far fewer survived the game.

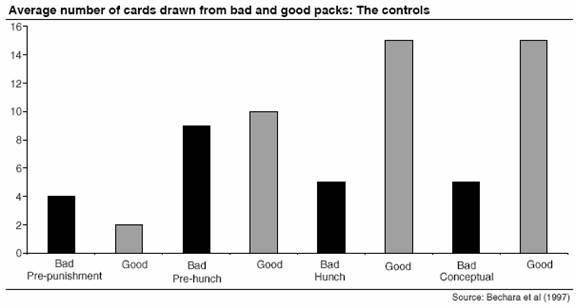

Now cast your eye over the two charts below. The first shows the number

of cards drawn from packs A and B (Bad) and C and D (good) in each phase

by the controls. In the pre-hunch phase they are already favouring the

good packs marginally. In the hunch phase, controls are clearly favouring

the good packs.

Now look at the performance of the patients. In the pre-hunch phase they

kept choosing the bad packs. As noted above there was no hunch phase.

And perhaps most bizarrely of all, even when they had articulated that

packs A and B were a bad idea, they still picked more cards from those

decks than from C and D! So despite "knowing" the correct conceptual answer,

the lack of ability to feel emotion severely hampered the performance

of these individuals.

However, similar games can be used to show that emotions can also handicap

us. Bechara et al8

play an investment game. Each player was given $20. They had to make a

decision each round of the game: invest $1 or not invest. If the decision

was not to invest, the task advanced to the next round. If the decision

was to invest, players would hand over one dollar to the experimenter.

The experimenter would then toss a coin in view of the player. If the

outcome was heads, the player lost the dollar, if the coin landed tails

up then $2.50 was added to the player's account. The task would then move

to the next round. Overall 20 rounds were played.

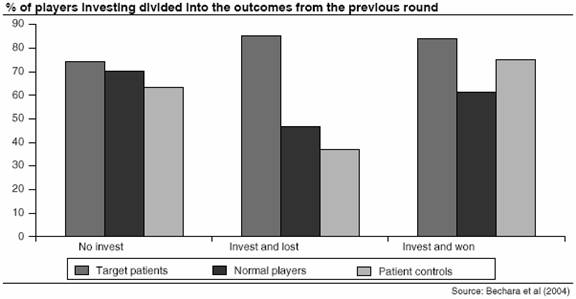

Bechara et al played this game with three different groups: 'normals',

a group of players with damage to the neural circuitry associated with

fear9

(target patients who can no longer feel fear), and a group of players

with other lesions to the brain unassociated with the fear neural circuitry

(patient controls).

The experimenters uncovered that the players with damage to the fear circuitry

invested in 83.7% of rounds, the 'normals' invested in 62.7% of rounds,

and the patient controls 60.7% of rounds. Was this result attributable

to the brain's handling of loss and fear? The chart below shows the results

broken down based on the result in the previous round. It shows the proportions

of groups that invested. It clearly demonstrates that 'normals' and patient

controls were more likely to shrink away from risk-taking, both when they

had lost in the previous round and when they won!

Players with damaged fear circuitry invested in 85.2% of rounds following

losses on previous rounds, whilst normal players invested in only 46.9%

of rounds following such losses.

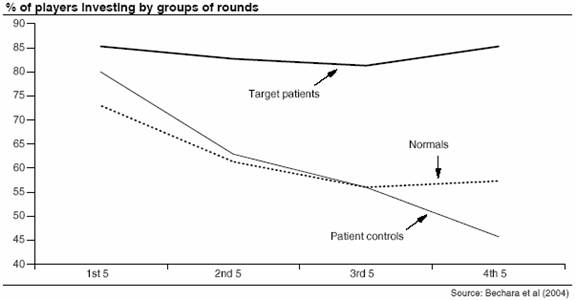

Bechara et al also found evidence of just how difficult learning actually

is. Instead of becoming more optimal as time moves on, normal players

actually become less optimal! (See chart below) For the record, a rational

player would, of course, play in all rounds.

So emotion can both help and hinder us. Without emotion we are unable

to sense risk, with emotion we can't control the fear that risk generates!

Welcome to the human condition!

Camerer et al10 argue that the influence of emotions depends upon the intensity of the experience. They note

At low level of intensity, affect appears to play a largely "advisory" role. A number of theories posit that emotions carry information that people use as an input into the decisions they face...

.... At intermediate level of intensity, people begin to become conscious of conflicts between cognitive and affective inputs. It is at such intermediate levels of intensity that one observes ...efforts at selfcontrol...

...Finally, at even greater levels of intensity, affect can be so powerful as to virtually preclude decision-making. No one "decides" to fall asleep at the wheel, but many people do. Under the influence of intense affective motivation, people often report themselves as being "out of control"... As Rita Carter writes in Mapping the Mind "where thought conflicts with emotion, the latter is designed by neural circuitry in our brains to win".

Camerer et al (2004)

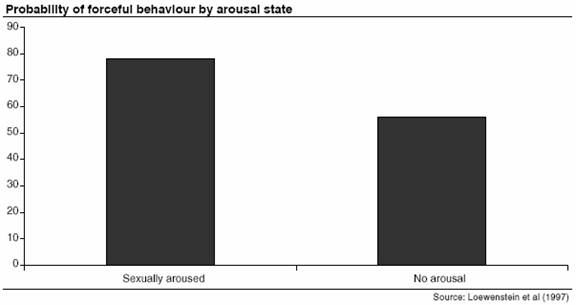

It is also worth noting that we are very bad at projecting how we will

feel under the influence of emotion - a characteristic psychologists call

hot-cold empathy gaps. That is to say, when we are relaxed and emotion

free, we underestimate how we would act under the influence of emotion.

For instance, Loewenstein et al11

asked a group of male students to say how likely they were to act in a

sexually aggressive manner in both a hot and cold environment. The scenario

they were given concerned coming home with a girl they had picked up at

a bar, having been told by friends that she had a reputation for being

"easy". The story went on that the participants and the girl were beginning

to get into physical genital contact on the sofa. The participants were

then told they had started to try and remove the girl's clothes, and she

says she wasn't interested in having sex.

Participants were then asked to assign probabilities to whether they would

(1) coax the girl to remove her clothes (2) have sex with her even after

her protests. The chart below shows the self reported probability of sexual

aggressiveness (defined as the sum of the probabilities of 1+2). Under

the no arousal condition there was an average 56% probability of sexual

aggression. After having been shown sexually arousing photos, the average

probability of aggression rose to nearly 80%!

Self-control is like a muscle

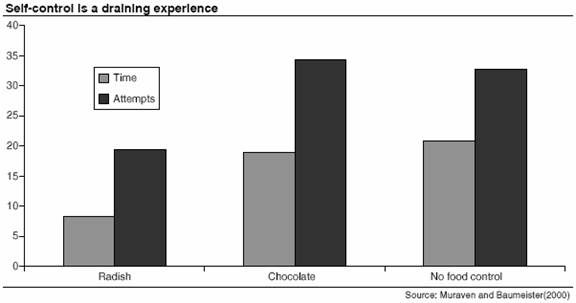

Unfortunately a vast array of psychological research12

suggests that our ability to use self-control to force our cognitive process

to override our emotional reaction is limited. Each effort at self-control

reduces the amount available for subsequent self-control efforts.

A classic example of Baumeister's work concerns the following experiment.

Participants are asked to avoid eating food for three hours before the

experiment began (timed so they were forced to skip lunch). When they

arrived they are put into one of three groups.

The first group were taken into a room which cookies had recently been

baked, so the aroma of freshly made chocolate chip delights wafted around.

This room also contained a tray laid out with the freshly baked cookies

and other chocolate delights, and a tray full of radishes. This group

were told they should eat as many radishes as they could in the next five

minutes, but they were also told they weren't allowed to touch the cookies.

A second group was taken to a similar room with the same two trays, but

told they could eat the cookies. The third group was taken to an empty

room.

All the food was then removed and the individuals were given problems

to solve. These problems took the form of tracing geometric shapes without

re-tracing lines or lifting the pen from the paper. The problems were,

sadly, unsolvable. However, the amount of time before participants gave

up and the number of attempts made before they gave up were both recorded.

The results were dramatic. Those who had eaten the radishes (and had therefore

expended large amounts of self control in resisting the cookies) gave

up in less than half the time that those who had eaten chocolate or eaten

nothing had done. They also had far less attempts at solving the problems

before giving up.

Baumeister (2003)13 concludes his survey by highlighting the key findings his research has found:

- Under emotional distress, people shift toward

favoring high-risk, high payoff options, even if these are objectively

poor choices. This appears based on a failure to think things through,

caused by emotional distress.

- When self-esteem is threatened, people become

upset and lose their capacity to regulate themselves. In particular,

people who hold a high opinion of themselves often get quite upset in

response to a blow to pride, and the rush to prove something great about

themselves overrides their normal rational way of dealing with life.

- Self-regulation is required for many forms of

self-interest behavior. When self-regulation fails, people may become

self-defeating in various ways, such as taking immediate pleasures instead

of delayed rewards. Self-regulation appears to depend on limited resources

that operate like strength or energy, and so people can only regulate

themselves to a limited extent.

- Making choices and decisions depletes this same

resource. Once the resource is depleted, such as after making a series

of important decisions, the self becomes tired and depleted, and its

subsequent decisions may well be costly or foolish.

- The need to belong is a central feature of human motivation, and when this need is thwarted such as by interpersonal rejection, the human being somehow ceases to function properly. Irrational and self-defeating acts become more common in the wake of rejection.

Baumeister (2003)

When I read this list it struck me just how many of these factors could

influence investors. Imagine a fund manager who has just had a noticeable

period of underperformance. He is likely to feel under pressure to start

to focus on high risk, high payoff options to make up the performance

deficit. He is also likely to feel his selfesteem is under threat as outlined

in 2 above. He is also likely to begin to become increasingly myopic,

focusing more and more on the short term. All of this is likely to be

particularly pronounced if the position run resulting in the underperformance

is a contrarian one. Effectively pretty much all the elements that lead

to the psychology of irrationality are likely to be present in large quantities.

Hard wired for the short term

Having explored the role of emotions and our ability to moderate their

influence, it is now time to turn to some examples of how powerful neuroscience

can be in helping us understand investor behaviour.

The first example suggests that we may be hard wired to focus on the short

term. Economists are all brought up to treasure the concept of utility14

- the mental reward or pleasure experienced. Traditionally, economists

view money as having no direct utility, rather it is held to have indirect

utility, that is, it can be used to purchase other goods and services,

which do provide direct utility.

Neuroscientists have found that money actually does have "utility", or

at least the brain anticipates receiving money in the same way that other

rewards are felt such as enjoying food or pleasure inducing drugs15.

The trouble is that the reward system for the brain has strong links to

the X-system. The anticipation of reward leads to the release of dopamine.

Dopamine makes people feel good about themselves, confident and stimulated.

Cocaine works by blocking the dopamine receptors in the brain, so the

brain can't absorb the dopamine, and hence nullify its effects. Because

the brain can't absorb the dopamine, it triggers further releases of the

drug. So when one takes coke, the dopamine release is increased, taking

the user to a high. Neuroscientists have found that the larger the anticipated

reward the more dopamine is released.

McClure et al16

have recently investigated the neural systems that underlie decisions

about delayed gratification. Much research has suggested that people tend

to behave impatiently today but plan to act patiently in the future. For

instance, when offered a choice between £10 today and £11

pounds tomorrow, many people choose the immediate option. However, if

asked today to choose between £10 in a year, and £11 in a

year and day, many people who went for the 'immediate' option in the first

case now go for the second option.

In order to see what happens in the brain when faced with such choices,

McClure et al measure the brain activity of participants as they make

a series of intertemporal choices between early and delayed monetary rewards

(like the one above). Some of the choice pairs included an immediate option,

others were choices between two delayed options. The results they uncovered

are intriguing.

When the choice pair involved an immediate gain the ventral stratum (part

of the basal ganglia), the medial orbitofrontal cortex, and the medial

pre-frontal cortex were all disproportionately used. All these elements

are associated with the X-system. McClure et al also point out that these

areas are also riddled by the midbrain dopamine system. They note "These

structures have consistently been implicated in impulsive behaviour, and

drug addiction is commonly thought to involve disturbances of dopaminergic

neurotransmission in these systems". Since money is a reward, the offer

of money today causes a surge in dopamine that people find very hard to

resist.

When the choice involved two delayed rewards, the pre-frontal and parietal

cortex were engaged (correlates of the C-system). The more difficult the

choice, the more these areas seemed to be used. Given the analysis of

the limits to self-control that was outlined above, perhaps we shouldn't

hold out too much hope for our ability to correct the urges triggered

by the X-system. All too often, it looks as if we are likely to end up

being hard wired for the short term.

Keynes was sadly right when he wrote "Investment based on genuine long-term

expectation is so difficult to-day as to be scarcely practicable".

Hard wired to herd

In the past, we have mentioned that there is strong evidence from neuroscience

to suggest that real pain and social pain are felt in exactly the same

places in the brain. Eisenberger and Lieberman17

asked participants to play a computer game. Players think they are playing

in a three way game with two other players, throwing a ball back and forth.

In fact, the two other players are computer controlled. After a period

of three way play, the two other 'players' began to exclude the participant

by throwing the ball back and forth between themselves. This social exclusion

generates brain activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula.

Both of which are also activated by real physical pain.

Contrarian strategies are the investment equivalent of seeking out social

pain. In order to implement such a strategy you will buy the things that

everyone else is selling, and sell the stocks that everyone else is buying.

This is social pain. Eisenberger and Lieberman's results suggest that

following such a strategy is really like having your arm broken on a regular

basis - not fun!

To buy when others are despondently selling and sell when others are greedily buying requires the greatest fortitude and pays the greatest reward

Sir John Templeton

It is the long-term investor, he who most promotes the public interest, who will in practice come in for the most criticism... For it is in the essence of his behaviour that he should be eccentric, unconventional and rash in the eyes of average opinion

John Maynard Keynes

Plasticity as salvation

All of this may make for fairly depressing reading. With emotions we can't

control ourselves, and without them we can't make decisions. We appear

to be doomed to chase short-term rewards and run with the herd. When we

try to resist these temptations we suffer subsequent declines in our ability

to exercise self-control. Not a pretty picture.

However, all is not lost. For many years it was thought that the number

of brain cells was fixed and they decayed over time. The good news is

that this isn't the case; We are capable of generating new brain cells

pretty much over our lifetime.

In addition, the brain isn't fixed into a certain format. The easiest

way of thinking about this is to imagine the brain as a cobweb. Some strands

of that cobweb are thicker than others. The more the brain uses a certain

pathway, the thicker the strand becomes. The thicker the strand, the more

the brain will tend to use that path. So if we get into bad mental habits,

they can become persistent.

However, we are also capable of rearranging those pathways (neurons).

This is how the brain learns. It is properly called plasticity. We aren't

doomed, we can learn, but it isn't easy!

1

Largely thanks to the work of Joseph LeDoux, see his wonderful book the

Emotional Brain for details.

2 Also know as the limbic system

3 For more on this see Paul Ekman's Emotions

Revealed. It is also worth noting that some developmental psychologists

have designed programs to teach children to recognise the physical signs

of emotions (such as anger) and then use thought to control those emotions.

See Mark Greenberg's work on PATHS (www.prevention.psu.edu/projects/PATHScurriculum.htm).

Much of the work has focused on teaching children to constrain their anger

- a modern day equivalent of counting to ten.

4 Epley and Gilovich (2001) Putting adjustment

back in the anchoring and adjustment heuristic, Psychological Science

Vol 12 No. 5

5 Gilbert and Gill (2000) The momentary

realist, Psychological Science, Vol. 11, No. 5

6 For more on this see Damasio (1994)

Descartes' Error

7 Bechara, Damasio, Tranel and Damasio

(1997) Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy,

Science Vol 275

8 Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, Loewenstein

and Shiv (2004) Investment behaviour and the dark side of emotion, unpublished

paper

9 Technically speaking this group had

suffered lesions to the amygdala, orbitofrontal and insular/somatosensory

cortex - all parts of the X system

10 Camerer, Loewenstein and Prelec (2004)

Neuroeconomics: How neuroscience can inform economics, Journal of Economic

Perspectives, forthcoming

11 Loewenstein, Nagin and Paternoster

(1997) The effect of sexual arousal on expectations of sexual forcefulness,

Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 34 No. 4

12 Muraven and Baumeister (2000) Self-regulation

and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle?

Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 126 No. 2 Or Baumeister (2003) The psychology

of irrationality: Why people make foolish, self-defeating choices, in

Brocas and Carrillo (2003) The Psychology of Economic Decision Volume

I: Rationality and Well-Being

13 Op cit

14 In fact psychologists have recently

argued that there is no single utility. Instead we have experienced utility

(actual liking from an outcome), remembered utility (memory of liking),

predicted utility (expected liking for the outcome in the future) and

decision utility (the actual choice of outcome).

15 Knutson and Peterson (2004) Neurally

reconstructing expected utility, forthcoming

16 McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein and

Cohen (2004) Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary

rewards, Science Vol. 306

17 Eisenberger and Lieberman (2004)

Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm system for physical and social

pain, Trend in Cognitive Sciences, Vol 8 No. 7

© Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein Securities Limited 2005