Entrepreneur and Business Resources

Integral Methods and Technology

Governance and Investor Responsibility

|

Bargain Hunter (or, It offers me protection)

By James Montier, Dresdner Kleinwort Benson

Regular readers will know that I am an unabashed value

investor. I like to buy cheap stocks. If you don't share this viewpoint,

or aren't open to be persuaded of the merits of such an approach, stop

reading now for what follows will only distress you. I am also an empiricist

at heart. Theories are all well and good, but sadly almost anything is

possible in theory. The only way to resolve theoretical impasses is to

examine the evidence. I am fond of quoting the words of Conan Doyle's

Sherlock Holmes "It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.

Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories

to suit facts" or "The temptation to form premature theories based upon

insufficient data is the bane of our profession".

So is there an empirical basis to my obsession with value? The short answer

is yes. The long answer takes up the rest of this note. My usual accomplice

and compatriot in adventures involving large amounts of data is Rui Antunes,

of our global quantitative team. It was with Rui's able help, that I embarked

upon an investigation of value strategies.

The methodology

We chose the MSCI indices as our universe. The stocks were ranked first

by trailing PE and then by actual reported earnings growth over the next

12 months (as if we could perfectly predict the future). Each sort resulted

in the formation of quintiles (with 20% of the universe in each quintile).

Given we sorted on two variables, we ended up with 25 portfolios of various

combinations of PEs and delivered earnings growth. The performance of

these portfolios was then tracked over the next 12 months. A sample of

our results can be seen in the table below.

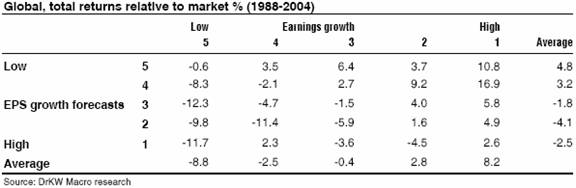

In this particular case, we are examining the global market and measuring

total returns1

relative to the average of the stocks in our universe. The tables

for each of the regions we examined are provided in full at the end of

this note for reference. Portfolio (5,5) represents the cheapest of the

value stocks with the lowest achieved earnings growth. Portfolio (1,1)

is the most expensive stocks with the highest delivered earnings growth.

Portfolio (1,5) is the cheapest basket of stocks with the highest earnings

growth and so forth2.

Does value work?

Several findings are apparent from examining the table. First (and of

foremost importance to me) is that buying cheap stocks did indeed outperform.

Simply buying an equal weighted basket (assuming equal distribution of

stocks across portfolios) of the lowest 20% of PEs within the MSCI World

index generated significant outperformance (9.7% p.a. on average). Such

a strategy would have only resulted in absolute losses in only five out

of the thirty years in our sample.

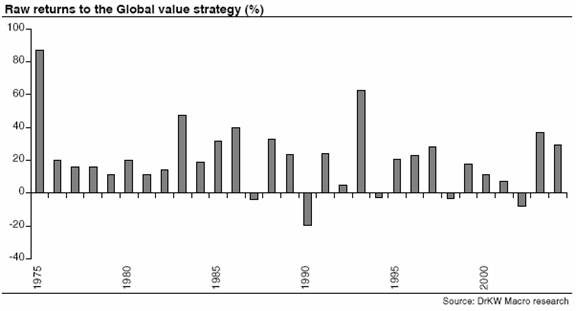

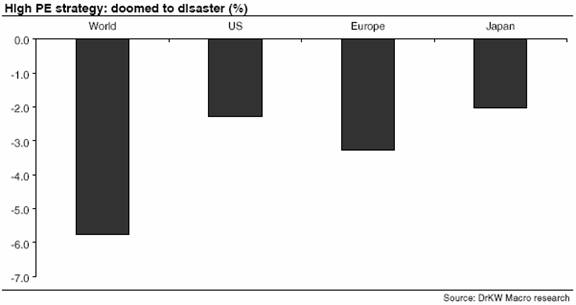

However such analysis ignores the fact that firms are not equally distributed

across all portfolios. The chart below shows the returns to a low PE strategy

in which the returns have been weighted by the actual distribution of

earnings in each of the categories. The results of the previous analysis

hold. The annual average raw return from a strategy of buying the lowest

20% of the MSCI World index ranked by PE was 20%. This represents a low

PE stock outperformance of the market of nearly 6% p.a!

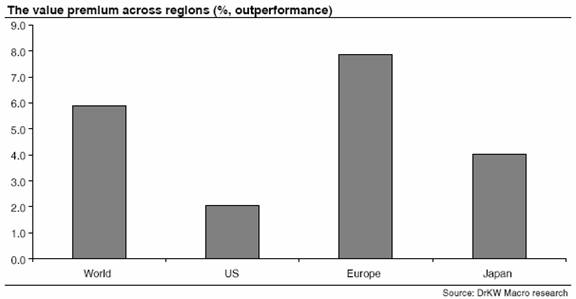

Similar patterns were found when we examined the regional breakdowns.

The chart below shows the outperformance of buying the bottom 20% by trailing

PE in the various markets we examined. There is a strongly consistent

value premium across countries/regions.

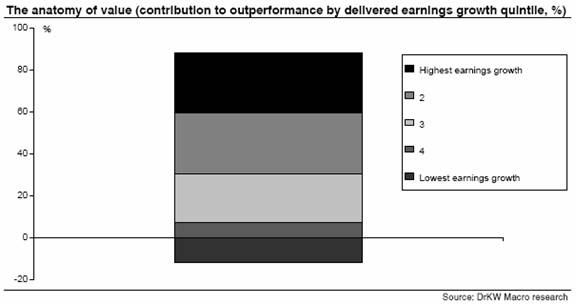

The anatomy of value

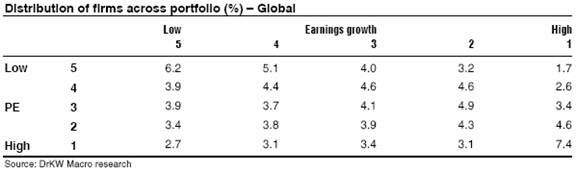

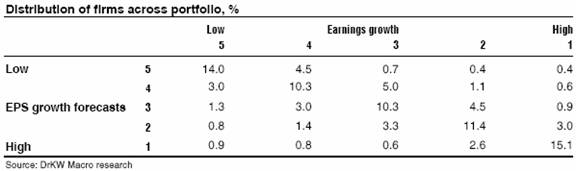

It is also noteworthy that only one of the value

portfolios resulted in underperformance (portfolio (5,5)). The table below

shows the distribution of firms across the portfolios. At the global level,

31% of the bottom 20% of the MSCI World index end up in the portfolio

that generates value underperformance. 6.2% of all stocks ended up in

portfolio (5,5), since by design the low PE stocks (portfolios (x,5) are

20% of the universe, we end up with 31% of the value universe in the underperforming

portfolio. So the majority of value stocks outperform.

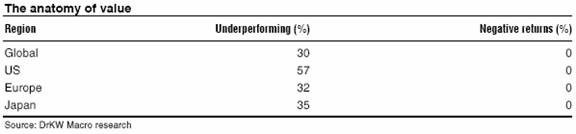

The table below shows the results for all the regions. None of the value

portfolios generate a negative absolute return (supporting our hypothesis

that value offers protection). However, in general, around 30-35% of the

lowest PE stocks seem to generate underperformance. The most extreme case

is the US where the value premium comes from a minority of stocks3.

This distribution suggests that value investing can be improved by

avoiding losers.

If the underperforming 30% could be identified ex ante then the returns

to value investing could be further enhanced. In previous work, we have

highlighted the findings of Piotroski (op cit), who uses a simple accounting

screen on financial stability to help avoid the value traps. An alternative

to this might be to use some measure of quality as our quant team has

developed in a series of notes.

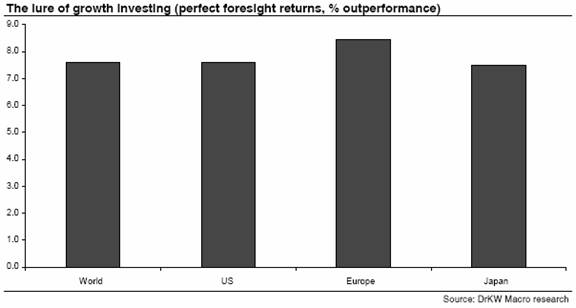

The siren of growth

If you had perfect foresight and knew exactly what earnings growth

would be achieved, and you bought the highest growth stocks regardless

of valuation, you would have outperformed by 11.3% p.a on average.

It is perhaps the hope or belief that investors can identify such equities

that sucks investors into growth investing, like sailors to the calls

of the sirens. However, the two most common behavioural biases are over-optimism

and over- confidence. We are all massively too sure about our ability

to predict the future.

The chart below shows the distribution weighted average returns if you

had had perfect foresight across the markets. This weighting drops the

return from 11.3% to a still very healthy 7.6% p.a. The eternal hope of

growth investing is clear. If only the winners could be picked ex ante!

Combine this hope of major outperformance with the mental vulnerability

to stories that we have outlined before and the lure of growth is obvious

for all to see.

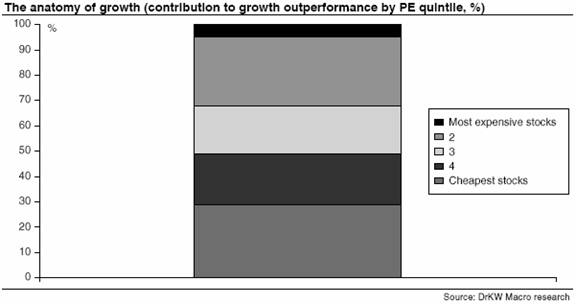

Growth doesn't mean ignoring valuation

The near monotonically declining performance of the delivered high growth

portfolios (column 1 in the table on page 2) should also be noted. That

is to say growth investors shouldn't ignore value. The cheaper the

stocks they buy, the better the performance achieved. Indeed the two

lowest PE bands provide over 50% of the total outperformance of the perfect

foresight growth premium.

All too often, growth-investing amounts to little more than buying

highly valued equities. The table above reveals that buying the

high PE stocks would have resulted in significant underperformance.

It is also interesting to note that to generate any outperformance from

buying high PE stocks would require you to pick those stocks that delivered

the very highest growth rates (Portfolio 5,1). Even if you could do this,

you would only manage to beat the very worst of the value stock baskets.

That is to say portfolio (1,1) only manages to beat portfolio (5,5). It

fails to beat all the other value portfolios (x,5).

The distribution table on page 3 also shows that within the high PE universe

only 37% of the stocks fall into portfolio (1,5). So growth stock investing

as proxied by buying expensive stocks is all about picking a minority

of winners.

It is also worth noting that buying highly valued stocks also carries

an enormous ‘torpedo' risk. The worst returns were seen in the high

PE stocks with the lowest delivered earnings growth (underperforming by

11.9% p.a. on average!).

The disappointing reality of growth

Of course, the natural response to these findings is to ask if we can

forecast growth. We decided to investigate exactly that. We were forced

to reduce the time span of our sample because of the lack of analysts'

forecasts going back. However, we were able to start this work in 1988,

giving us 17 years worth of data.

Once again, two-way sorts into quintiles were conducted. This time we

replaced the PE with the forecast growth rate from analysts. So, we are

comparing the forecast of earnings growth with the outturn. And then tracking

the returns delivered by each of the portfolios.

The table below shows the global summary of this analysis. Just to be

clear, portfolio (1,5) is the portfolio that contains the stocks with

the highest actual earnings growth but that were expected to have the

lowest earnings growth, and so forth.

Unsurprisingly, the best stocks were the ones that had the lowest expectations

but delivered the highest outcome (portfolio 1,5), outperforming by nearly

11% p.a. The worst were those with the highest expectations and the lowest

outturns (portfolio 5,1), underperforming by nearly 12% p.a on average.

Neither of these findings is likely to shock anyone. However, the table

also shows the difficulty of picking growth stocks ex ante. If you

had invested an equal amount into the 20% of stocks with the highest

forecast earnings growth then you would have underperformed by 2.5% p.a.

on average!

In contrast, if you had invested in the 20% of stocks with the lowest

growth expectations then you would have outperformed by 4% p.a. on average.

The role of expectations in this process couldn't be much clearer.

It is far easier to surprise on the upside if the expectations are

low in the first place.

Analyst accuracy?

Of course, using these simple averages assumes an equal distribution of

stocks within each portfolio. That is akin to saying that analysts are

completely useless at forecasting the earnings growth. That strikes even

me as slightly harsh (and I am certainly not known as an apologist for

analysts as those who have seen one of my behavioural finance presentations

can attest).

But, we can also use our data to get some insight into the forecast accuracy

of analysts. The table below shows the distribution of forecasts and outturns

for the MSCI World index. Effectively the diagonals represent the points

where analysts were correct. The good news for analysts is that the majority

of forecasts are in the same quintile as the outturn. For instance, there

is a 75% overlap between those firms that analysts forecast to have the

highest earnings growth, and those that actually do have the highest earnings

growth.

Sounds impressive doesn't it? But it still means that one in four of their

forecasts is off the mark. More importantly, the table on page 4 shows

that the outperformance generated by those firms with high expected and

delivered growth is relatively small at 2.6% p.a. Whereas the 25% of firms

the analysts say are going to have the highest earnings growth, but don't

deliver have an average return of -3.7% p.a. The combined effect is that

the weighted average return on the high growth forecast portfolio is

an outperformance of 0.9%.

What about the low growth realm? There is a 70% overlap between those

firms that the analysts think will have the lowest earnings growth, and

those that do indeed have the lowest earnings growth. Indeed if we weight

the returns by the distribution accuracy of analysts, those with low

forecasts generate an outperformance of 0.9%. This is not statistically

different from the high growth result. So effectively analyst forecasts

can't tell us very much at all! They certainly can't help us identify

growth stocks as a source of significant outperformance.

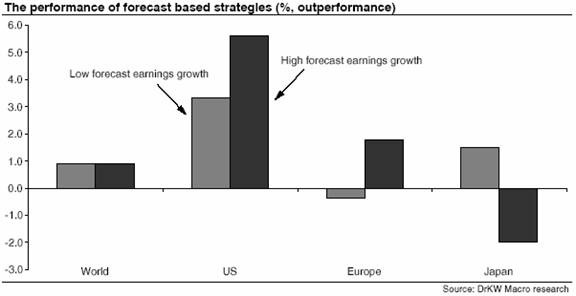

The chart below shows the regional breakdowns of the weighted performance

of forecast growth portfolios. In Japan you could have made money by shorting

the stocks with high forecast earnings growth! Elsewhere, following the

forecasts of analysts would have generated positive returns on average.

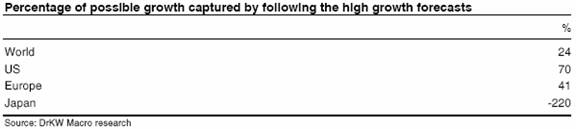

An alternative way to evaluate the power of following the forecasts is

to ask how much the forecast strategy would have managed to capture of

the idealised strategy of knowing exactly what growth was actually going

to be delivered. The table below shows the percentage of the maximum attainable

return that was actually achieved if one had bought the 20% of stocks

with the highest growth forecasts from analysts.

With the exception of the US, the results are sobering. At the global

level, following the analysts' forecasts of growth would have captured

just 24% of the total growth premium available. In Europe this improves

to 40%, still not an impressive performance. In Japan, the forecasts are

actually a better contrarian indicator than having any value in their

own right! In the US, the strategy of following the analysts did much

better, delivering 70% of the total possible return to the perfect foresight

premium.

Value vs. Growth

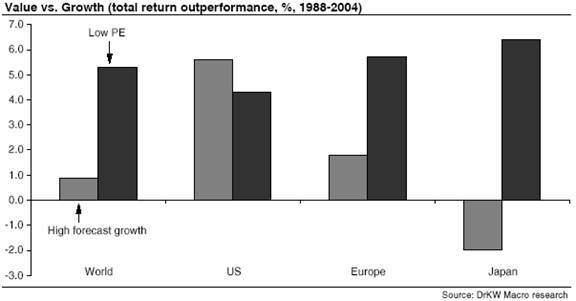

So to the crucial question...value or growth? The chart below shows the

weighted total return outperformance figures for the value and growth

forecast strategies for the regions since 1988.

In general the results show the massive superiority of being a ‘bargain

hunter'. Ben Graham's concept of a margin of safety is still sound today.

Buying cheap stocks offers significant protection against any potential

bad news.

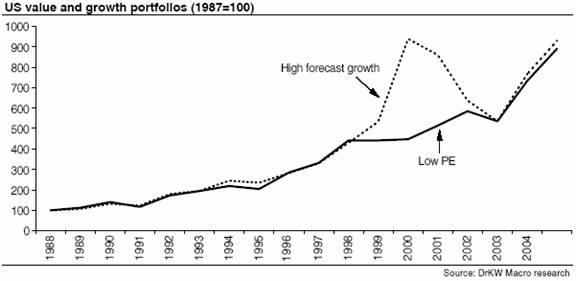

Only in the US does the return on following the analyst's growth forecasts

exceed the return from buying cheap stocks. However, the chart below shows

the time path of the two portfolios. The impact of the bubble years becomes

immediately obvious.

The US value and growth portfolios have actually generated very similar

returns. The value portfolio has a CAGR of 13.7%, and the high forecast

growth portfolio has a CAGR of 14.0% since 1988. Effectively there has

been little to choose between the two strategies. Although it should be

noted that the value portfolio has a markedly lower standard deviation

of returns (17.7% for the value portfolio, against 25.1% from the growth

portfolio). Thus on a risk adjusted measure value would have significantly

outperformed growth. So much for value stocks being riskier!

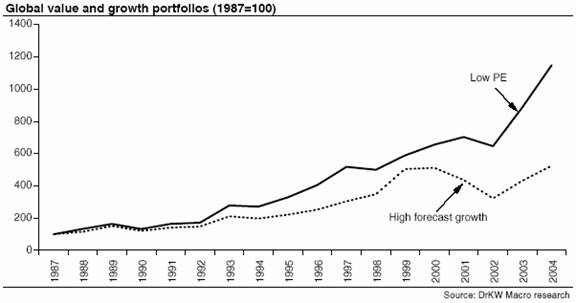

The chart below shows the portfolio returns from the global portfolios,

the performance of the low PE portfolio alongside the high forecast earnings

growth portfolio. The high forecast earnings growth portfolio earns a

10.2% CAGR p.a., whilst the low PE portfolio generates a 15.4% CAGR p.a.

1 The analysis was done in terms of both price and total returns. The results were invariant to the specification used.

2 The portfolio labels always go across the table (columns) and then down the rows.

3 Consistent with the findings of Piotroski (2000) Value Investing: The use of historical financial information to separate winners and losers, The Journal of Accounting Research, Vol 38